Introduction

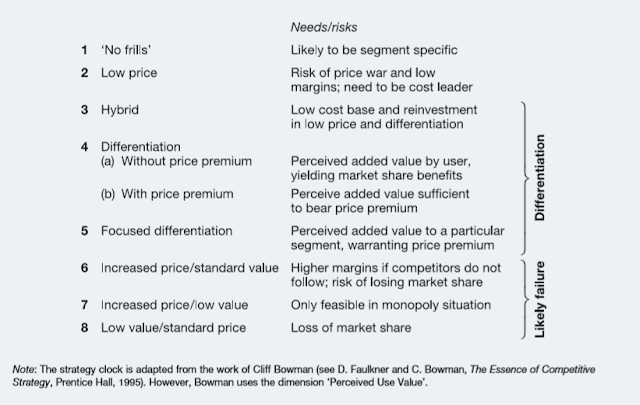

The discussion of each of these strategies that follows also acknowledges the importance of an organisation’s costs – particularly relative to competitors. But it will be seen that cost is a strategic consideration for all strategies on the clock – not just those where the lead edge is low price. Since these strategies are ‘market facing’ it is important to understand the critical success factors for each position on the clock. Customers at positions 1 and 2 are primarily concerned with price, but only if the product/service benefits meet their threshold requirements. This usually means that customers emphasise functionality over service or aspects such as design or packaging. In contrast, customers at position 5 require a customised product or service for which they are prepared to pay a price premium.

The volume of demand in a market is unlikely to be evenly spread across the positions on the clock. In commodity-like markets demand is substantially weighted towards positions 1 and 2. Many public services are of this type too. Other markets have significant demand in positions 4 and 5. Historically professional services were of this type. However, markets change over time. Commodity-like markets develop value-added niches which grow as disposable incomes rise.

For example, this has occurred in the drinks market with premium and speciality beers. And customised markets may become more commodity-like particularly where IT can demystify and routinise the professional content of the product – as in financial services. So the strategy clock can help managers understand the changing requirements of their markets and the choices they can make about positioning and competitive advantage. Each position on the clock will now be discussed.

Strategic Clock Diagram

1. Price-based strategies (routes 1 and 2)

Route 1 is the ‘no frills’ strategy, which combines a low price with low perceived product/service benefits and a focus on a price-sensitive market segment. These segments might exist because of the following:

2. (Broad) Differentiation strategies (route 4)

The next option is a broad differentiation strategy providing products or services that offer benefits different from those of competitors and that are widely valued by buyers.4 The aim is to achieve competitive advantage by offering better products or services at the same price or enhancing margins by pricing slightly higher. In public services, the equivalent is the achievement of a ‘centre of excellence’ status, attracting higher funding from government (for example, universities try to show that they are better at research or teaching than other universities). The success of a differentiation approach is likely to be dependent on two key factors:

3 The hybrid strategy (route 3)

A hybrid strategy seeks simultaneously to achieve differentiation and low price relative to competitors. The success of this strategy depends on the ability to deliver enhanced benefits to customers together with low prices whilst achieving sufficient margins for reinvestment to maintain and develop bases of differentiation. It is, in effect, the strategy Tesco is seeking to follow. It might be argued that, if differentiation can be achieved, there should be no need to have a lower price, since it should be possible to obtain prices at least equal to the competition, if not higher. Indeed, there is a good deal of debate as to whether a hybrid strategy can be a successful competitive strategy rather than a suboptimal compromise between low price and differentiation. If it is the latter, very likely it will be ineffective. However, the hybrid strategy could be advantageous when:

4. Focused differentiation (route 5)

A focused differentiation strategy provides high perceived product/service benefits, typically justifying a substantial price premium, usually to a selected market segment (or niche). These could be premium products and heavily branded, for example. Manufacturers of premium beers, single malt whiskies and wines from particular chateaux all seek to convince customers who value or see themselves as discerning of quality that their product is sufficiently differentiated from competitors’ products to justify significantly higher prices. In the public services, centres of excellence (such as a specialist museum) achieve levels of funding significantly higher than more generalist providers. However, focused differentiation raises some important issues:

A choice may have to be made between a focus strategy (position 5) and broad differentiation (position 4). A firm following a strategy of international growth may have to choose between building competitive advantage on the basis of a common global product and brand (route 4) or tailoring its offering to specific markets (route 5).

Tensions between a focus strategy and other strategies. For example, broadbased car manufacturers, such as Ford, acquired premier marques, such as

Market changes may erode differences between segments, leaving the organisation open to much wider competition. Customers may become unwilling to pay a price premium as the features of ‘regular’ offerings improve. Or the market may be further segmented by even more differentiated offerings from competitors. For example, ‘up-market’ restaurants have been hit by rising standards elsewhere and by the advent of ‘niche’ restaurants that specialise in particular types of food.

5 Failure strategies (routes 6, 7 and 8)

A failure strategy is one which does not provide perceived value for money in terms of product features, price or both. So the strategies suggested by routes 6, 7 and 8 are probably destined for failure. Route 6 suggests increasing price without increasing product/service benefits to the customer, the strategy that monopoly organisations are accused of following.

Unless the organisation is protected by legislation, or high economic barriers to entry, competitors are likely to erode market share.

Route 7 is an even more disastrous extension of route 6, involving the reduction in product/service benefits whilst increasing relative price.

Route 8, reduction in benefits whilst maintaining price, is also dangerous, though firms have tried to follow it. There is a high risk that competitors will increase their share substantially. There is also another basis of failure, which is for a business to be unclear as to its fundamental generic strategy such that it ends up being ‘stuck in the middle’ – a recipe for failure.

Route 1 is the ‘no frills’ strategy, which combines a low price with low perceived product/service benefits and a focus on a price-sensitive market segment. These segments might exist because of the following:

- The existence of commodity markets. These are markets where customers do not value or discern differences in the offering of different suppliers, so price becomes the key competitive issue. Basic foodstuffs – particularly in developing economies – are an example.

- There may be price-sensitive customers, who cannot afford, or choose not, to buy better-quality goods. This market segment may be unattractive to major providers but offers an opportunity to others (Aldi, Lidl and Netto in Illustration 6.1, for example). In the public services funders with tight budgets may decide to support only basic-level provision (for example, in subsidised spectacles or dentistry).

- Buyers have high power and/or low switching costs so there is little choice – for example, in situations of tendering for government contracts.

- The strategy offers an opportunity to avoid major competitors. Where major providers compete on other bases, a low-price segment may be an opportunity for smaller players or a new entrant to carve out a niche or to use route 1 as a bridgehead to build volume before moving on to other strategies. Route 2, the low-price strategy, seeks to achieve a lower price than competitors whilst maintaining similar perceived product or service benefits to those offered by competitors. Increasingly this has been the competitive strategy chosen by Asda (owned by Wal-Mart) and Morrisons in the UK supermarket sector. In the public sector, since the ‘price’ of a service to the provider of funds (usually government) is the unit costs of the organisation receiving the budget, the equivalent is year-on-year efficiency gains achieved without loss of perceived benefits. Competitive advantage through a low-price strategy might be achieved by focusing on a market segment that is unattractive to competitors and so avoiding competitive pressures eroding price. However, a more common and more challenging situation is where there is competition on the basis of price, for example in the public sector and in commodity-like markets. There are two pitfalls when competing on price:

- Margin reductions for all. Although tactical advantage might be gained by reducing price this is likely to be followed by competitors, squeezing profit margins for everyone.

- An inability to reinvest. Low margins reduce the resources available to develop products or services and result in a loss of perceived benefit of the product. So, in the long run, both a ‘no frills’ strategy and a low-price strategy cannot be pursued without a low-cost base. However, low cost in itself is not a basis for advantage. Managers often pursue low cost that does not give them competitive advantage. The challenge is how costs can be reduced in ways which others cannot match such that a low-price strategy might give sustainable advantage.

2. (Broad) Differentiation strategies (route 4)

The next option is a broad differentiation strategy providing products or services that offer benefits different from those of competitors and that are widely valued by buyers.4 The aim is to achieve competitive advantage by offering better products or services at the same price or enhancing margins by pricing slightly higher. In public services, the equivalent is the achievement of a ‘centre of excellence’ status, attracting higher funding from government (for example, universities try to show that they are better at research or teaching than other universities). The success of a differentiation approach is likely to be dependent on two key factors:

- Identifying and understanding the strategic customer. The concept of the strategic customer is helpful because it focuses consideration on who the strategy is targeting. For example, for a newspaper business, is the customer the reader of the newspaper, the advertiser, or both? They are likely to have different needs and be looking for different benefits. For a branded food manufacturer is it the end consumer or the retailer? It may be important that public sector organisations offer perceived benefits, but to whom? Is it the service user or the provider of funds? However, what is valued by the strategic customer can also be dangerously taken for granted by managers, a reminder of the importance of identifying critical success factors

- Identifying key competitors. Who is the organisation competing against? For example, in the brewing industry there are now just a few major global competitors, but there are also many local or regional brewers. Players in each strategic group need to decide who they regard as competitors and, given that, which bases of differentiation might be considered. Heineken appears to have decided that it is the other global competitors – Carlsberg and Anheuser-Busch, for example. SABMiller built its global reach on the basis of acquiring and developing national brands and competing on the basis of local tastes and traditions, but has more recently also acquired Miller to compete globally.

- The difficulty of imitation. The success of a strategy of differentiation must depend on how easily it can be imitated by competitors.

- The extent of vulnerability to price-based competition. In some markets customers are more price sensitive than others. So it may be that bases of differentiation are just not sufficient in the face of lower prices. Managers often complain, for example, that customers do not seem to value the superior levels of service they offer. Or, to take the example of UK grocery retailing, Sainsbury’s could once claim to be the broad differentiator on the basis of quality but customers now perceive that Tesco is comparable and seen to offer lower prices.

3 The hybrid strategy (route 3)

A hybrid strategy seeks simultaneously to achieve differentiation and low price relative to competitors. The success of this strategy depends on the ability to deliver enhanced benefits to customers together with low prices whilst achieving sufficient margins for reinvestment to maintain and develop bases of differentiation. It is, in effect, the strategy Tesco is seeking to follow. It might be argued that, if differentiation can be achieved, there should be no need to have a lower price, since it should be possible to obtain prices at least equal to the competition, if not higher. Indeed, there is a good deal of debate as to whether a hybrid strategy can be a successful competitive strategy rather than a suboptimal compromise between low price and differentiation. If it is the latter, very likely it will be ineffective. However, the hybrid strategy could be advantageous when:

- Much greater volumes can be achieved than competitors so that margins may still be better because of a low-cost base, much as Tesco is achieving given its market share in the UK.

- Cost reductions are available outside its differentiated activities. For example, IKEA concentrates on building differentiation on the basis of its marketing, product range, logistics and store operations, but low customer expectations on service levels allow cost reduction because customers are prepared to transport and build its products.

- Used as an entry strategy in a market with established competitors. For example, in developing a global strategy a business may target a poorly run operation in a competitor’s portfolio of businesses in a geographical area of the world6 and enter that market with a superior product at a lower price to establish a foothold from which it can move further.

4. Focused differentiation (route 5)

A focused differentiation strategy provides high perceived product/service benefits, typically justifying a substantial price premium, usually to a selected market segment (or niche). These could be premium products and heavily branded, for example. Manufacturers of premium beers, single malt whiskies and wines from particular chateaux all seek to convince customers who value or see themselves as discerning of quality that their product is sufficiently differentiated from competitors’ products to justify significantly higher prices. In the public services, centres of excellence (such as a specialist museum) achieve levels of funding significantly higher than more generalist providers. However, focused differentiation raises some important issues:

A choice may have to be made between a focus strategy (position 5) and broad differentiation (position 4). A firm following a strategy of international growth may have to choose between building competitive advantage on the basis of a common global product and brand (route 4) or tailoring its offering to specific markets (route 5).

Tensions between a focus strategy and other strategies. For example, broadbased car manufacturers, such as Ford, acquired premier marques, such as

- A hybrid strategy seeks simultaneously to achieve differentiation and a price lower than that of competitors

- A focused differentiation strategy seeks to provide high perceived product/service benefits justifying a substantial price premium, usually to a selected market segment (niche)

- Possible conflict with stakeholder expectations. For example, a public library service might be more cost efficient if it concentrated its development efforts on IT-based online information services. However, this would very likely conflict with its purpose of social inclusion since it would exclude people who were not IT literate.

Market changes may erode differences between segments, leaving the organisation open to much wider competition. Customers may become unwilling to pay a price premium as the features of ‘regular’ offerings improve. Or the market may be further segmented by even more differentiated offerings from competitors. For example, ‘up-market’ restaurants have been hit by rising standards elsewhere and by the advent of ‘niche’ restaurants that specialise in particular types of food.

5 Failure strategies (routes 6, 7 and 8)

A failure strategy is one which does not provide perceived value for money in terms of product features, price or both. So the strategies suggested by routes 6, 7 and 8 are probably destined for failure. Route 6 suggests increasing price without increasing product/service benefits to the customer, the strategy that monopoly organisations are accused of following.

Unless the organisation is protected by legislation, or high economic barriers to entry, competitors are likely to erode market share.

Route 7 is an even more disastrous extension of route 6, involving the reduction in product/service benefits whilst increasing relative price.

Route 8, reduction in benefits whilst maintaining price, is also dangerous, though firms have tried to follow it. There is a high risk that competitors will increase their share substantially. There is also another basis of failure, which is for a business to be unclear as to its fundamental generic strategy such that it ends up being ‘stuck in the middle’ – a recipe for failure.

Comments

Post a Comment